In a recent research project, MnDOT sought to validate a smartphone app designed to guide pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired through signalized and unsignalized intersections. The project succeeded in showing the app’s effectiveness in tests at six intersections in Stillwater, Minnesota.

As smartphones have become increasingly common, MnDOT has supported research projects that make use of them in many ways, including enhancing safety on the state’s highways and city streets. Several projects have used smartphone apps that leverage the device’s capabilities with other intersecting technologies to increase driver information and safety. Others have focused on pedestrian safety.

“This was a good project, with the innovative use of technology that we hope will benefit individuals with visual impairments,” said Michael Fairbanks, signal operations engineer, MnDOT Metro District.

Increased safety of pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired was the objective of a previous MnDOT project that developed a smartphone app that could audibly direct those pedestrians through work zone sidewalks. The University of Minnesota researchers who developed that app knew they could do much more in this area with smartphone features. They developed a smartphone app that could access traffic signal data. Using that data in concert with several smartphone capabilities, they constructed a smartphone app that could audibly assist pedestrians with visual impairments through signalized and unsignalized intersection crosswalks. MnDOT was interested in examining the efficacy of this smartphone app, called PedNav, in a controlled, real-world setting. This project sought to validate the researchers’ system.

What Was Our Goal?

The overall objective of this project was to develop a more accurate and accessible mobility solution for pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired to safely navigate through the urban environment. The project had three specific goals: install a system that could access traffic controllers’ data and broadcast it through a wireless network, refine the smartphone-based system that accesses and displays traffic information, and validate the system’s performance by testing it at signalized and unsignalized intersections.

What Did We Do?

The smartphone app was tested in Stillwater, Minnesota, where MnDOT operates the signalized intersections. Six intersections were chosen: four signalized and two unsignalized.

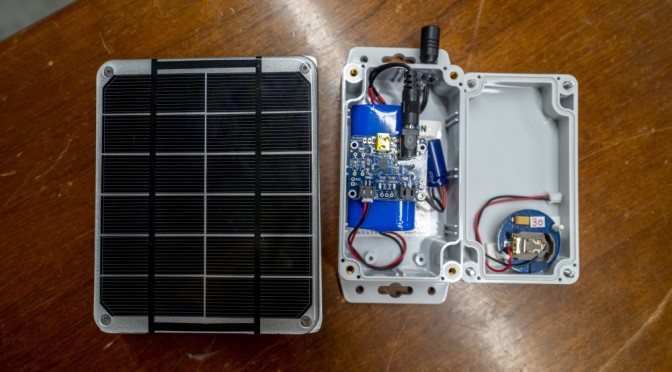

The testing setup involved several technical operations. Researchers created a digital map in a database to store the test area’s intersection and signal information. Then they deployed a network of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons attached to traffic signal and other posts in the test area to help users who are blind or visually impaired identify their location. The app uses the BLE beacons to help locate and inform users that crossing data is provided at the right location.

With assistance from MnDOT traffic control engineers, researchers installed hardware within each of the four intersection signal controller cabinets. These units would broadcast real-time traffic signal phasing and timing (SPaT) information. The research team deployed a data collection system, Smartlink from Miovision, which enabled them to collect the SPaT data through MnDOT’s secure infrastructure network. A cloud server would then broadcast SPaT data through a subscription-based cellular network to the smartphone app to provide real-time signal information to pedestrian users.

Researchers evaluated the wireless traffic network’s security through a private network set up for this and future projects that could require a similar secure wireless environment.

The app initially received SPaT data through a hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP)-based interface, but an unacceptable 3- to 5-second lag time occurred with the interface. Researchers then used a Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) interface, which was fast enough for the timely transmission of real-time traffic signal data.

“Our system allows transportation agencies to provide more accessible traffic information for people who are visually impaired, thus improving their mobility and independence in using the transportation system,” said Chen-Fu Liao, senior research associate, University of Minnesota Department of Civil, Environmental and Geo-Engineering.

Finally, the researchers repeatedly tested the app at the six intersections for position and message accuracy. One screen tap gave users orientation and geometry information, such as “Heading west to cross Oak Street, 4-lane” as a text-to-speech message. Two taps provided signal information; a walk phase request sent to the signal controller would generate a response such as “Wait for walk signal.” A vibration and signal announcement guided users; for example, “Harvard. Walk sign is on. 20 seconds to cross.”

What Was the Result?

Researchers tested the phone location, wireless data transmission lag time and correctness of the displayed SPaT information (visual and audio). The phone-reported position accuracy averaged 5.6 meters. Text and audible message correctness tests showed the system provided 132 of 137 messages correctly (96%) on intersection geometry and signal status information. The five incorrect messages were due to incorrect measurements by the phone’s digital compass, which can be distorted if the user is near a large ferrous object. The system functioned effectively in the real-world test; its concepts and technologies were validated.

What’s Next?

While MnDOT has not determined how it may seek to use PedNav in the future, researchers developed steps that would facilitate its implementation. These included creating guidelines for wireless traffic data communication in a connected community; identifying intersections where there is a gap in knowledge for pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired; and creating digital maps that include sidewalks, intersections and work zones.